The Angel Who Comes Bearing Pain. The Confrontational Oeuvre of Arnon Grunberg

Arnon Grunberg has received the prestigious PC Hooft Prize 2022 for his extensive and diverse oeuvre. In his work, the writer combines horror and tenderness, satire with sincerity. He challenges readers with his confrontational worlds, in which characters succumb to oppressive systems. Grunberg himself calls the overarching theme in his oeuvre ‘lived despair’. Portrait of a prolific writer with a mission.

Almost naked, Arnon Grunberg stands facing the audience. In the intimate hall, the discomfort is palpable. For the short 51-year-old man, who has written all his life, not danced, and also for his audience. We look, and he looks back. The silent connection that ensues is awkward, yet strangely moving. The dance show that Grunberg performed in recent months with, among others, the poet Charlotte van den Broeck, had no care for grace or beauty. What mattered was the relationship with the other and with us, the audience. And what that could mean.

Although Arnon Grunberg did not win the PC Hooft Prize for his dance technique, this most recent performance forms an integral part of his artistry. Just as in his twenty novels, hundreds of essays, articles, and manic letters, in short, everything for which he did receive this lifetime achievement award, Grunberg challenges his audience. Not because he is a typical narcissistic writer, who only exists when he is seen. On the contrary. What we see or hear is invariably something that should have been kept secret. By telling it anyway, Grunberg draws the audience unwillingly into his world of pain.

And painful it is. Whether his characters murder their mothers or their children, torture their loved ones, execute innocent hostages, or writhe around naked in their own filth: they all draw the reader into a world that is extremely confrontational.

Reviewers and readers alike have often found that world difficult to deal with. The aggression of Beck in The Asylum Seeker, the perversion of François in Gstaad

or the xenophobia of Hofmeester from Tirza. Grunberg’s characters are emotionally detached men, always watching out for ‘danger’.

However, anyone who accuses the writer of creating ‘sterile’ characters overlooks the fact that it is precisely to their own love that these men fall prey. It is caring that kills them – the care for a sick or dependent woman: their mother, daughter or sister, a Namibian child, or a psychiatric patient. For example, Beck from The Asylum Seeker feels responsible for his dying lover, whom he wants to comfort: ‘He held her like a father held his child’. In Grunberg’s novels, the sick Other represents the unliveable, that which moves towards death. Embracing it or avoiding it, either will result in destruction.

The sick Other represents the unliveable, that which moves towards death

That is the essentially tragic pattern of Grunberg’s novels, in which the hero tries not to heed the call of the other, but in doing so destroys them both. If the protagonist tries to flee, he is invariably punished: just think of the prisons or other institutions in which the aforementioned Beck and François but also Mehlman (Fantoompijn, 2000; Phantom Pain, 2000) and Sam Ambani (De man zonder ziekte, 2012; The Man Without Illness) end up.

Does it follow that Grunberg’s novels are merely private stories about damaged individuals? By no means. Grunberg’s characters flounder under the impact of oppressive systems, from colonialism to capitalism. The clinical picture they present is not the result of personal abnormalities, but of societal violence. Not just individuals, but all of humanity has become ‘invalid’ – traumatised by its own barbarism.

Statements Grunberg makes about ‘human beings’ are therefore very similar to how traumatised victims are theorised. ‘To be human means to recognise that trust in the world has been irreparably broken,’ the author wrote. In many ways, not only the individual, but the whole structure of ‘civilization’ appears to be fundamentally damaged. The Shoah, the horror of the extermination of six million Jewish people in the heart of Europe, is the most important symbol of this. And so it is in his oeuvre, for him, as the son of a German-Jewish father and mother, who both survived Auschwitz.

Grunberg’s characters flounder under the impact of oppressive systems, from colonialism to capitalism

‘Just a footnote to my mother’s memoirs’, is how Arnon Grunberg described his immense output. ‘I am not saying that my oeuvre is exclusively about the war’, he explains: ‘at most that there are gaps in the memories, in the story of my mother and my father, that need to be filled in. Best with fiction.’

Filling in the holes made by the 20th century: this momentous task may explain the urgency of Grunberg’s writing, which began with a debut at age 23: Blue Mondays (1994). In an earlier sketch, Grunberg had written about his family: ‘This must remain absolutely secret (…). Nobody may know what is happening here. It would be best if no one knew that my parents existed and no one knew that I lived here in this house.’

The fact that he subsequently wrote a novel in which he made public the most intimate and humiliating details, from his mother’s aggression and his father’s diarrhoea to his own brothel visit, is characteristic of Grunberg’s relationship with his audience. Literature was a survival mechanism because he could make witnesses of us.

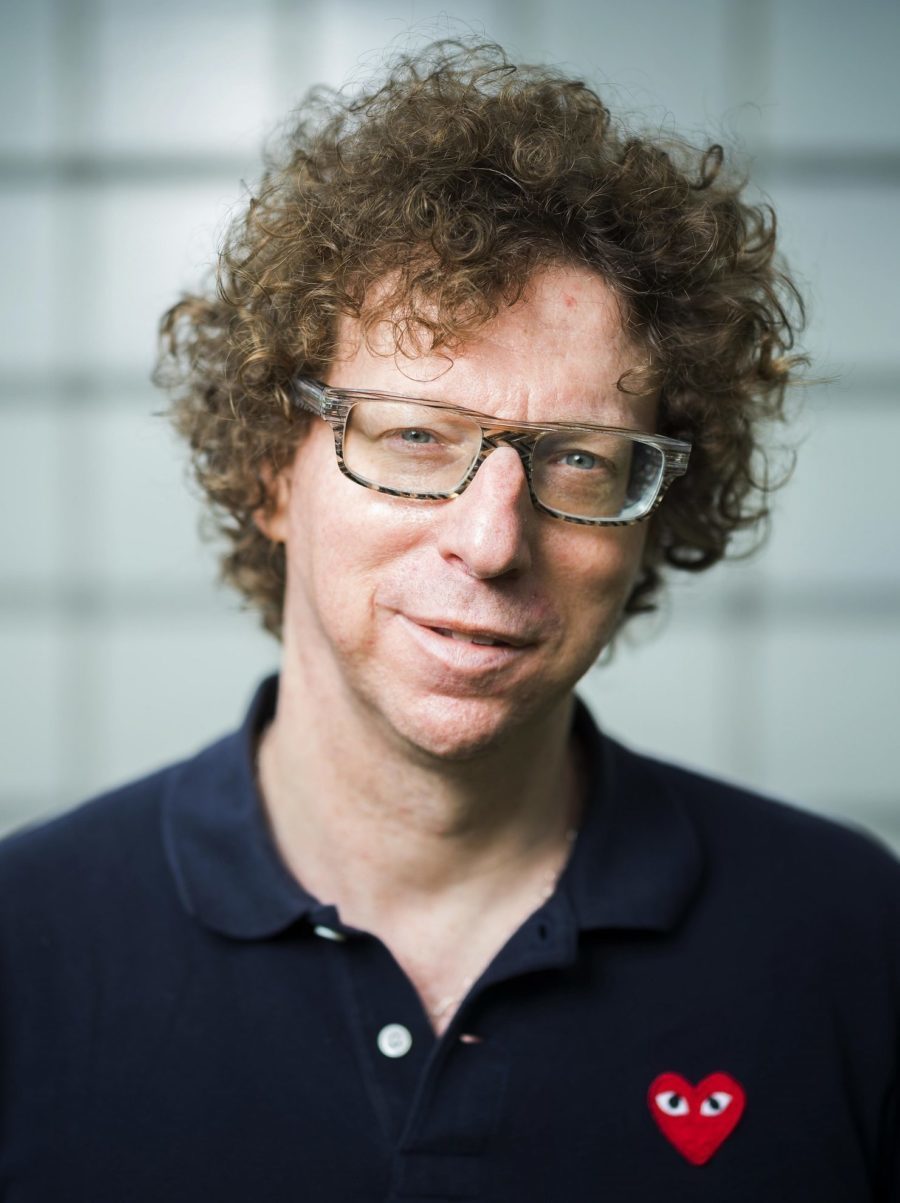

Arnon Grunberg

Arnon Grunberg© Merlijn Doomernik

After 2003, those autobiographical and furious, rebellious texts made way for more universal ethical political explorations, such as De man zonder ziekte (The Man Without Illness). The stories are no longer set in Amsterdam, where the author was born, but in South America, Switzerland, and Israel. The main characters are often editors, architects, psychiatrists or scientists, cultural professions that act as a metaphor for being a writer.

The question in these novels is not only how writing (and especially being read) can save the protagonist, but what art can do at all in the light of violent European history. What does it mean to write about humanity, if at the same time there are enough reasons to give up hope in humanity?

What does it mean to write about humanity, if at the same time there are enough reasons to give up hope in humanity?

In Grunberg’s novels, writing successively turns out to be a form of prostitution, of outdated humanism, an expression of a perverse lust for fame, of theft, of repetition and translation, of capitalist complicity and, above all, always: of evading the ethical duty towards one’s neighbour, who expects you to care instead of to write. In this view of the world, healing – individually or socially – is not attainable.

The truth of Grunberg’s novels amounts to exposing any fixed moral position as fictitious in itself: in this way literature can offer an analysis of the ‘cynical utopia’ in which, according to Grunberg, we live. The writer does everything he can to ‘infect’ the reader with the disease that is his reality, as he said in his Albert Verwey lecture, which was published as Het verraad van de tekst (The Betrayal of the Text, 2009): ‘Excellent literature can provide healing, as far as I’m concerned. But whoever accepts this has also to face the downside: that same literature can make you sick.’ It is the truth about ourselves that is sickening, he continues: ‘Truth – in the sense of self-knowledge, knowledge of the others who circle around us like satellites and the world in which all this takes place, even if it is or appears to be unliveable – is preferable to lies that supposedly can make us happy.’

How terrifying that truth apparently is for some, was demonstrated by the presenters of the tv-show about books, Brommer op zee, where Arnon Grunberg was recently the main guest. ‘Lived despair’ is how he himself described the key theme in his work. But the presenters quickly moved the topic on. The conversation had to be about ‘play’, about ‘sexual transgression’, or for heaven’s sake about the portraits on the back flap of his books. Even when Grunberg recommended the Auschwitz author Tadeusz Borowski, or talked about concentration camps, or about his mother who in his eyes had always remained ‘a girl of 12’ (her age in 1939), the presenters ignored his prompts. After all, literature should be fun.

So viewers did not discover how Grunberg pictures the future of his writing. Where will the search for ‘meaning’ take him, now that he has arrived at point zero: dance, which is only body? Whatever his next novel will be about, it is clear that the audience will continue to play an indispensable role in his oeuvre. ‘People have no right to happiness,’ Grunberg wrote to his mother on 3 June 2001 (a letter that we were of course allowed, even had to read, in the magazine Humo) and he continues: ‘People have a right to pain. I see myself as an angel who must give people that to which they are entitled.’